Abraham Lincoln was president from March 1861 until his assassination in April 1865. Abraham Lincoln is found on the $5 bill. The US Penny (1¢) also has the portrait of Abraham Lincoln. The life of Abraham Lincoln is justifiably celebrated every year. But that life is perhaps even more interesting than many celebrants may know. On one occasion, Douglas attempted to buffalo Lincoln by making allusions to his lowly start in life. He told a gathering that the first time he met Lincoln, it had been across the counter of a general store in which Lincoln was serving. “And an excellent bartender he was too,” Douglas concluded. This is a joke that actual President Lincoln told: There was an American ambassador to England after the revolutionary war, and his bitter hosts wanted to antagonize him. So they got a portrait of President Washington, and had it hung in the privy (toilet).

By Amy Cavanaughin Foodon Feb 12, 2013 8:00PM

Back before he was President, Abraham Lincoln was a lawyer. And before he was a lawyer, he was something else entirely—a bartender.

Holders of the nation's highest office have often had a close relationship with booze, as George Washington established the nation's largest whiskey distillery in 1797 and Thomas Jefferson brewed his own beer. Andrew Jackson's inaugural party in 1829 was so legendary that we still drink the orange punch partygoers consumed (and you can find it on the menu at Big Jones). But Lincoln was the only president who was also a licensed bartender.

Lincoln was co-owner of Berry and Lincoln, a store/drinking establishment in New Salem, Illinois, where he lived from 1831 to 1837. He first arrived there on a flat boat when he was 22 and en route to New Orleans. His boat got stuck there and after visiting New Orleans, he returned to New Salem and decided to stay. He worked as a store clerk, served in a militia, and unsuccessfully ran for office. Then, in 1833, he opened a small store.

In January 1833, he partnered with his friend from his militia days, William F. Berry, to purchase a small store, which they named Berry and Lincoln. Stores could sell alcohol in quantities greater than a pint for off-premises consumption, but it was illegal to sell single drinks to consume at the store without a license. In March 1833, Berry and Lincoln were issued a tavern, or liquor, license, which cost them $7 and was taken out in Berry's name. Stores that sold liquor to consume on the premises were called groceries.

So what did they serve? Half pints of French brandy for 25 cents, peach brandy for 18.75 cents, and apple brandy for 12 cents. Half pints of Holland gin cost 18.75 cents, while domestic gin was 12.5 cents. Wine cost 25 cents, rum was 18.75 cents, and whiskey was 12.5 cents. They could also sell food—breakfast, dinner, and supper were each 25 cents—and put people up for the night. Lodging was 12.5 cents per night, and horses could stay for 25 cents, with feed going for 12.5 cents. Takeout meals for stage passengers cost 37.25 cents, and they also sold beer and cider.

Lincoln's foray into the world of booze was short-lived—Berry was apparently an alcoholic and took advantage of the new liquor license to drink while he was working in the store. Lincoln spent more time dealing with customers and his down time reading, and they fell into debt. In April 1833, he sold his interest in the store to Berry and was appointed Postmaster of New Salem on May 7, 1833. Berry died two years later, and Lincoln assumed the debts from the business. It wasn't until 1848, when Lincoln was a congressman, that he was able to pay off the whole debt.

Lincoln remained in New Salem, and he studied law and earned a legal license. In 1837, he realized that his opportunities in New Salem were limited and he moved to Springfield, where he thought he'd have better luck with his law practice and have a chance to get involved in politics.

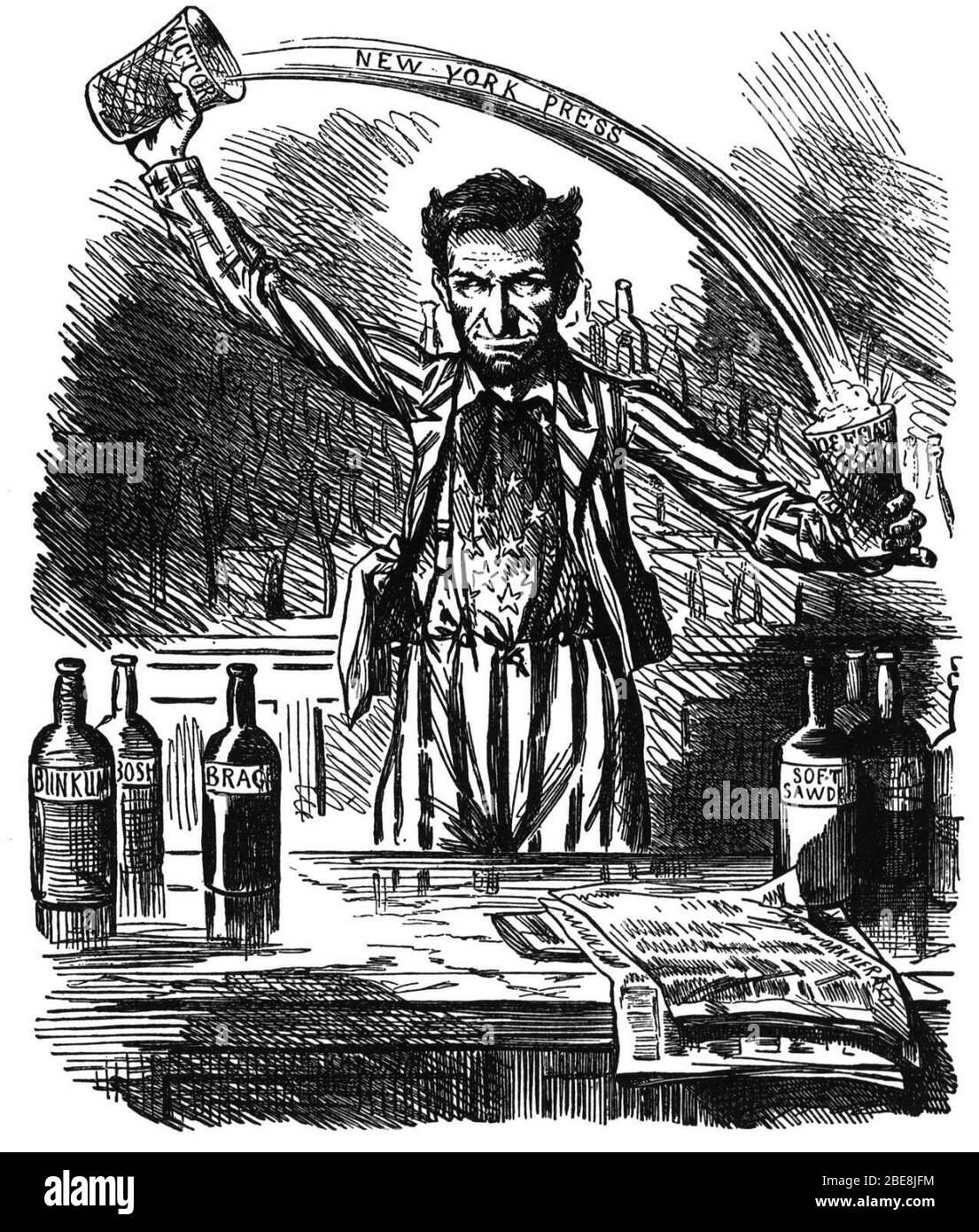

Once he got into politics, Lincoln denied selling alcohol by the drink. At the first of the Lincoln-Douglas debates in Ottawa on August 21, 1858, Douglas poked fun at Lincoln's early job. Judging by the transcripts, these debates were hilarious.

Abe Lincoln Law Partner

There were many points of sympathy between us when we first got acquainted. We were both comparatively boys, and both struggling with poverty in a strange land. I was a school-teacher in the town of Winchester, and he a flourishing grocery-keeper in the town of Salem. (Applause and laughter.)… I met him there, however, and had sympathy with him, because of the up-hill struggle we both had in life. He was then just as good at telling an anecdote as now. ('No doubt.') He could beat any of the boys wrestling, or running a foot-race, in pitching quoits or tossing a copper; could ruin more liquor than all the boys of the town together. (uproarious laughter.)

Lincoln retorted:

Now I pass on to consider one or two more of these little follies. The Judge is woefully at fault about his early friend Lincoln being a 'grocery keeper.' [Laughter.] I don't know as it would be a great sin, if I had been; but he is mistaken. Lincoln never kept a grocery anywhere in the world. [Laughter.] It is true that Lincoln did work the latter part of one winter in a little still house, up at the head of a hollow. [Roars of laughter.]

Today is Lincoln's 204th birthday, so let's raise a glass of brandy to the President's days behind the stick.

Best of Chicagoist

The Best Vegan-Friendly Restaurants In ChicagoThe Best Restaurants For Vegetarians In ChicagoThe Best 'Anti-Brunch' Breakfast Spots In Chicago, Where You Can Eat All Week4 Chicago Spots With Can't-Miss Pumpkin Spice LattesOur Readers Picked The Best Burger Spot In Chicagoby Philip Jett

Abraham Lincoln Bartender

Most American citizens know that President Abraham Lincoln was fatally shot on April 14, 1865, just after the Civil War ended. However, it’s what happened to Lincoln afterward that intrigues me.

On May 4, 1865, after weeks of lying in state and then in repose in twelve cities, the sixteenth president was “laid to rest” inside a receiving vault at Oak Ridge Cemetery near Lincoln’s home in Springfield, Illinois, until the Lincoln Tomb could be completed. Rather than resting, however, Lincoln’s body was moved seventeen times and his coffin opened five times before finally resting in peace thirty-six years later inside a steel cage beneath two tons of concrete poured ten feet high over his coffin. Astonishing. Even Dracula didn’t move that often.

You might say part of the reason for all the shuffling began while Lincoln was president. He signed a bill in 1862 establishing a national currency and, ironically, on the morning of his assassination, signed legislation creating the U.S. Secret Service to capture counterfeiters. The best engraver of counterfeit plates was Benjamin Boyd, who worked for a Chicago syndicate run by James “Big Jim” Kinealy (spellings vary). The Secret Service eventually captured Boyd, who was sentenced to prison in 1876. Boyd’s imprisonment wrecked Big Jim’s counterfeiting business so he devised a plan to obtain a governor’s pardon for Boyd, plus $200,000 (about $4.6 million today).

Big Jim recruited bartender Terrence Mullen and petty counterfeiter Jack Hughes to snatch Abraham Lincoln’s body from his Springfield tomb on election night while everyone was in town waiting for the results. They’d then transport the martyred president by wagon to an area southeast of Chicago and bury him in the sand dunes near Lake Michigan. There was only one problem with the plan: they knew nothing about body snatching. So Big Jim recruited Louis Swegles, who claimed to be the best body snatcher around, and Bill Nealy to drive the getaway wagon.

The four men boarded a train to Springfield on the night of November 6, 1876, carrying a carpetbag full of body snatching tools. Unknown to Big Jim’s gang, several other men boarded the rear of the same train with more men boarding the following morning. They included Chicago Secret Service chief, Patrick Tyrrell, former US Secret Service chief, Elmer Washburn, and two Pinkerton detectives. Big Jim had unwittingly recruited himself two Secret Service informants, Swegles and Nealy.

The following night two miles outside of Springfield, Tyrrell and his men hid inside the Lincoln Tomb and waited in complete darkness in their stocking feet. The body snatchers, half of whom were working for the Secret Service, arrived at the cemetery two hours later. They discovered that Lincoln’s sarcophagus rested behind a barred door chained shut by a single padlock. After the gang filed through the lock and raised the lid of the sarcophagus, they were unable to lift the 500-pound mahogany and lead-lined coffin out, so they cut the end of the sarcophagus away. At last, the body snatchers began dragging Lincoln’s coffin from the sarcophagus. Then, they heard a gunshot. One of Tyrrell’s men nervously hidden in the dark had accidentally discharged his pistol.

Tyrrell raced into the burial chamber and discovered Lincoln’s coffin, but “no fiend was there.” He spotted the silhouettes of two men outside and fired. They fired back. “Chief, we have the devils up here!” Tyrrell yelled to Washburn. “Tyrrell, is that you?” yelled back another. The lawmen had been shooting at each other while the crooks escaped. Tyrrell later remarked that it was “one of the most unfortunate nights I have ever experienced.”

Mullen and Hughes were eventually apprehended back in Chicago. Because body snatching was not a federal or Illinois crime at that time, they were convicted of attempting to steal Lincoln’s $75 coffin and spent only a year in state prison. Unfortunately for Lincoln, that was not the end of it.

Concerned about other potential grave robbers, the tomb’s caretaker, John Carroll Power, and some friends decided they’d safeguard Lincoln by secretly burying his body in the basement. While digging, they discovered that the water table was too high so they laid the heavy coffin on wood, covered it with scraps of lumber, and swore themselves to secrecy. The men left the Great Emancipator and Savior of the Union beneath a woodpile in a dank basement for two years until the secret group (who fancifully christened themselves the Lincoln Guard of Honor) buried Lincoln in an unmarked spot where the water table was lower, only to dig him up two days later to make sure he was inside before reburying him. There he lay for four more years.

When Lincoln’s wife, Mary, died in 1882, her coffin was placed inside the Lincoln Tomb during the funeral ceremony only to be removed later by the Lincoln Guard and buried in the basement beside her husband. The men then piled debris over the two graves. Five years later, President and Ms. Lincoln finally made it out of the basement only to be moved from one tomb chamber to another. Their coffins were even placed inside a concrete-lined pit dug outside the tomb when unbelievably in 1899, the massive Lincoln Tomb and its giant obelisk were dismantled due to a faulty foundation. When the tomb was rebuilt in 1901, Robert Lincoln could stand the musical gravesites no longer. He ordered his father’s coffin placed inside a steel cage, lowered into a ten foot chamber, and covered with two tons of concrete. A heavy granite cenotaph bearing Lincoln’s name sits on the marble floor above him.

One hundred and seventeen years later, Abe still rests alone beneath 4,000 pounds of concrete and steel inside the tomb. Or does he?

It should be noted that a former gardener at Mount Vernon attempted to steal George Washington’s head from the family crypt thirty-one years after his death only to make off with the wrong cranium. The estate immediately began construction of a more secure tomb for the first president and his family.

PHILIP JETT is a former corporate attorney who has represented multinational corporations, CEOs, and celebrities from the music, television, and sports industries. He is the author of The Death of an Heir: Adolph Coors III and the Murder That Rocked an American Brewing Dynasty. Jett now lives in Nashville, Tennessee.

Tags: Lincoln, president's day, US history, us presidents